Latest Post

Showing posts with label release. Show all posts

Showing posts with label release. Show all posts

06:38

TANZANIA

Zanzibar University

MUFTI SHEIKH HASSAN BIN AMEIR (1880 - 1979)

Written By mahamoud on Thursday, 26 December 2013 | 06:38

Seminar on

The Role of Educated Youth to Muslim Society

27thFebruary – 4th March 2004

ORGANISED BY

ZANZIBAR UNIVERSITY

WORLD ASSEMBLY OF MUSLIM YOUTH

(WAMY)

MUFTI SHEIKH HASSAN BIN AMEIR

(1880 - 1979)

The Moving Spirit of Muslim Emancipation in Tanganyika

(1950 – 1968)

Speaker

Mohamed Said

Venue

Introduction

The name of Mufti Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir like the names of many other Muslim patriots is omitted from the political history of Tanzania

Having accomplished his role as a patriot and a symbol of mass mobilisation under TANU during the struggle he resigned from politics soon after Tanganyika Zanzibar

In the same breath relations between Muslims and BAKWATA to say the least has been lukewarm. Muslims perceive BAKWATA as a puppet organisation and just to mention the name leaves a bad taste in the mouth. To refer to a Muslim as a BAKWATA Muslim is like calling a Christian a disciple of Judas Iscariot who betrayed Jesus for thirty pieces of silver. As to Nyerere, history is yet to judge him. But one can not be knowledgeable to all this in the absence of the political history of Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir.

There are however, contrary voices disputing Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir’s political carrier. These voices are originating from some of his students questioning his role in politics. Students of Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir prefer to remember him as a brilliant ‘ulamaa’, an outstanding translator of the Qur’an[2] and not as a politician. Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir’s ‘silsila’ goes back to Sayyidna A’li b. Abu T’alib and Rasuli Lahi (SAW). Understandingly his students do not want to taint this with what they perceive as ‘trifles’. But reality and history takes exception to this. This stand if allowed to flourish would wipe out and obscure an important period in Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir’s life and hence erase a significant chapter in the nation’s history. Along with it, the country will also lose his thoughts, teachings and aspirations, which made him what he is in the history of Tanganyika Tanganyika

Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir - The Scholar Foot-Soldier, 1940 -1950

In 1940 when Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir left Zanzibar for Tanganyika Tanganyika from where he could spread the message of Islam to the neighbouring countries of Congo , Nyasaland , Rwanda and Burundi Tanganyika Congo , Rwanda and Burundi seeing masses of their subjects reverting to Islam declared him a prohibited immigrant in all their colonies and he was therefore forcefully evicted back to Tanganyika Dar es Salaam to Bujumbura in Burundi

Back in Tanganyika Africa . When nationalist politics began in Tanganyika

The Years of Tabligh and Politics, 1950 - 1961

Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir’s political carrier began much earlier when he was travelling around the country establishing centres (zawiyya). Probably unknown to his students that they were being prepared as foot soldiers for an imminent onslaught on the colonial government. However, Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir came into prominence in 1950 when he was elected into the TAA-Political Subcommittee and hence became one of the signatories[6]to the memorandum on constitutional development presented by TAA to the Governor of Tanganyika, Sir Edward Twining.[7]The task of this committee among other issues was to clandestinely prepare the ground for formation of TANU to free Tanganyika Tanganyika

Open politics and mass mobilisation to agitate for independence in Tanganyika Pemba Street Dar es Salaam

The name ‘Yuda’ coined by TANU had direct relationship with Judas Iscariot from Christian scriptures, the traitor who betrayed Jesus for thirty pieces of silver. The problems which TANU encountered were mainly from colonial government or those inspired by it using fellow Africans as puppets to try to derail the movement. It was the belief of Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir that the survival of Muslims as a people and Islam as a religion rested in the total overthrow of the colonial government and the strategy to achieve that goal was through national unity. It was from this cue from Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir that Nyerere and with the help of the Elders Council was able to establish in TANU the nationalist-secularist ideology.

A very critical obstacle to national unity was thus averted. Had TANU succumbed to sectarian politics of insisting that since Muslims were the most discriminated upon by colonialism and were dominant in politics and should therefore assume leadership in the party, this would have been divisive and counter productive to the movement. Christians would have been alienated and probably the colonial government in its ‘divide and rule’ tactics would have encouraged them to form a rival party. This new party certainly would not have been pro - Islam. The only power to benefit from such rivalry would have been the British and the road to independence would not have been smooth. It would have been fraught with factional violence as is the case in all countries where sectarian politics reign supreme.

Nyerere was a familiar face at the 'darsa' of Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir in down town Dar es Salaam Tanganyika Dar es Salaam

A trying period for Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir was in 1958 when TANU was in preparation for the first general election ever to be conducted in Tanganyika Tanganyika

We cannot go into the details of the Tripartite Voting as it is beyond the scope of this paper but suffice to state that against the stand of the majority and his own party, Nyerere worked behind the scene to win support and therefore participate in the election. Nyerere argued for participation and won the day thus paving the way for the educated Christians to be voted to the Legislative Council because they possessed the necessary qualifications. To some this was seen as Nyerere’s ploy to promote fellow Christian into positions of power in Tanganyika Tanganyika

A faction in TANU opposing the party’s stand on the election resigned and formed a rival party, the All Muslim National Union of Tanganyika (AMNUT) to safeguard Muslim interests. One of the demands of AMNUT was that the British should delay independence until such time that Muslims would be educated enough to enable them assume important positions in the government. AMNUT published pamphlets and articles warning Muslims of the dangers facing Islam in post - colonial Tanganyika

Once again as he had done in 1955 Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir had to deal with a religious factor in politics which this time was more volatile and more threatening to national unity than the previous one. The problem threatened to split the country and the party into two contending forces. Mufti Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir supported Nyerere’s stand to participate in the election notwithstanding the domination of Christian candidates. The Mufti of Tanganyika refused to endorse AMNUT’s stand and ignored the general Muslim sentiments. It was a bold and wise decision. It was as if the Mufti had pronounced a silent ‘fatwa.’ Other sheikhs in the country supported Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir’s stand. AMNUT, it was declared, would cause animosity among the people and Muslims should support TANU until independence was achieved. But the most devastating blow came from Tanga. Sheikhs and Qur’an teachers in Tanga signed a joint declaration opposing AMNUT. The declaration stated that AMNUT would create danger. The sheikhs reiterated that they would support TANU until independence was achieved because they had confidence with the objectives of TANU. [12] With such a bombardment from the people which AMNUT claimed to be representing their interest, AMNUT could not endure. Muslims never supported AMNUT until when it was banned, by the government following the enactment of the law in 1965, which established Tanganyika

The first attempt by Muslims of Tanganyika to form their own political party to fight for their rights therefore failed. Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir believed AMNUT would have encouraged factionalism and therefore create disunity. The country whithered the storm and Nyerere, a Roman Catholic went on to become the first Prime Minister of Tanganyika at independence in 1961 through a very strong Muslim support. Muslim had shown their trust in Nyerere. They believed as Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir had believed that Nyerere would be a just ruler and would exercise justice to all without discrimination, fear or favour.

The Rise and Fall of ‘Daa’wat Islamiyya’ (Muslim Call), 1961 -1968

After independence in 1961 Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir resigned from politics and formed ‘Daa’wat Islamiyya’ (Muslim Call), according to his own words, to serve Islam better. After independence was achieved Muslims thought their chance for development had at last arrived. The struggle had reached its logical conclusion. In 1962 a pan-territorial congress of all Muslim organisations was called in Dar es Salaam Tanganyika Tanganyika Dar es Salaam East Africa . That decision was as good as a declaration of war against the Church.

The Church felt these decisions by Muslims were a threat to its own future in Tanganyika Tanganyika

Sheikh Hassan bin Amir’s first displeasure with the government was in 1961. During independence celebrations the Catholic Church issued and distributed independence memento depicting Christian symbols associating the Church with the independence struggle. Soon after, the government established relations with the Vatican

Attempts to Dismantle Muslim Unity, 1963 – 1968

The First Attempt, 1963

Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir was seen as a stumbling - block to Christian hegemony. Parallel with this the EAMWS, the powerful organisation which united Muslims of East Africa had also to be demobilised. Suddenly and without warning throughout the country, particularly in urban centres were Muslims where a majority, there seemed to be a set plan to harass and intimidate Muslim activists. There were negative overtones from the government against Islam and Muslims contrary to what Muslims had envisaged before independence. Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir was not unaware of all this. He decided to open a new frontline to counter these new developments.

Following the dissolution of the Elders Council it was obvious that Nyerere had abandoned Muslims as allies and was cultivating a new political power base. Encouraged by his success in abolishing the Elders Council in TANU Nyerere introduced another issue to the party, that the EAMWS should also be dissolved and a local Muslim organisation be formed. Nyerere failed to get TANU Central Committee’s support on this one.

When the EAMWS called the Second Muslim Congress in that year the main agenda was the government’s hostility to Islam. This meeting would go down in history as one in which Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir took Nyerere head on. The crux of the matter was that Nyerere had secretly proposed to certain Muslims in the EAMWS executive to propose dissolution of the EAMWS so that they have a new local organisation to be led by an African instead of the Aga Khan.

Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir saw through Nyerere’s proposal as a strategy to ‘divide and rule’ and hence sabotage Muslim unity. He knew Nyerere wanted to divide Muslims along racial lines and thus weaken African Muslims economically because Aga Khan’s financial contribution to the EAMWS was very significant. It was Aga Khan’s resources which supported ‘tabligh’, built schools and mosques for Muslims. Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir was now sure that Nyerere had turned out to be an enemy of Islam. What he had heard about him after independence were not rumours but hard facts. Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir without flinching, directed the congress to oppose Nyerere’s proposal. Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir had taken the bull by the horns.

Nyerere was invited to close the meeting and Mufti Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir took the opportunity to speak his mind. But he did not stand in person to speak because he was not a platform politician. Sheikh Hassan’s domain was confined within the precinct of his ‘madras’ and the pulpit. One of his lieutenants from the provinces spoke, and not mincing words warned Nyerere to be careful with Muslims because it was they who had put him in power. (There was nothing which Nyerere loathed more than be reminded that he had a debt to pay to Muslims of Tanganyika). Nyerere knew that was not the EAMWS leadership speaking or even for that matter the very speaker facing him from the floor. It was Mufti Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir speaking and warning him. Worse, the person who delivered the message was none other than Sheikh Bilal Rehani Waikela, TANU founder member and a patriot who fought for independence of Tanganyika

In April, 1964 Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir led a strong delegation of the EAMWS consisting of Sheikh Said Omar Abdallah, EAMWS President Tewa Said Tewa, the Secretary Abdul-Aziz Khaki and others for a tour of Islamic countries to solicit financial support to build the Islamic University agreed in the Islamic Congress of 1962 and to establish relations with the Muslim world. This was the first time that Muslims in Tanganyika Tanganyika Cairo East Africa to receive that honour.

In January 1964, an army mutiny occurred in Tanganyika Rifles. Nyerere took this opportunity to detain[13]EAMWS leaders in the provinces and other prominent sheikhs, some very close to Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir, on the pretext that they had instigated the mutiny. Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir’s s network built for almost three decades and which he had depended for the new struggle for Muslim emancipation was targeted and was in retreat and in other places in disarray. Many of his lieutenants and students some of them prominent scholars found themselves behind bars. Al this harassment withstanding, Muslim unity under the EAMWS remained intact.

The Second Attempt, 1966

In 1966 the EAMWS held its annual conference in Arusha. A separatist group emerged from Tanzania Tanzania Kenya Uganda Tanzania Tanzania East Africa umma. This, it was observed, would weaken not only Tanzanian Muslims, but the Muslim community in East Africa . It was clear from the outset that there was pressure from Nyerere to effect these changes. It soon became clear that Nyerere was working towards disbanding the EAMWS using few hand-picked Muslims within the EAMWS. The aim was to form a new organisation over which the government could have some control. This had to be done in order to contain Muslims as a political force and hence cripple them.

Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir was fully aware of these new developments and he too laid out his strategy to counter Nyerere’s machinations. Sheikh Hassan was aware that Nyerere was planning to cripple Muslim efforts for equal power sharing with Christians. Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir began to issue Friday ‘khutbas’ which were distributed throughout the country and were read in mosques in the provinces during Friday prayers. Mufti Sheikh Hassan’s thoughts were heard from pulpits of different mosques in Tanganyika

Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir realised that the struggle for real independence was far from finished. He now had a new enemy which he had not anticipated to fight. The irony of it all is the fact that he had moulded the enemy by the sweat of his own brow and that of the general Muslim community in Tanganyika

The Final Attempt, 1968

In the month of October, 1968 TANU and government mass media through a series of stories made the people believe that the EAMWS was facing a crisis of massive proportion. The most telling one was that of one unknown primary school teacher from Bukoba by the name of Adam Nasibu who announced through the state radio and the party press that his region, Bukoba, was splitting from the EAMWS.[14]Overnight this obscure school teacher became a hero of sorts as the mass media of the party and government built up his image and publicised what came to be known as the Muslim ‘crisis’. For three months Adam Nasibu shared with Nyerere the front page of the TANU dailies under its editor, Benjamin William Mkapa. The EAMWS was accused of not being a true representative of African Muslims and therefore had no relevance to Tanzania

A trio strategy against the EAMWS was in top gear. Benjamin Mkapa, the Editor of ‘The Nationalist’ would publish any statement against the EAWMS, then Martin Kiama, the Director of Radio Tanzania

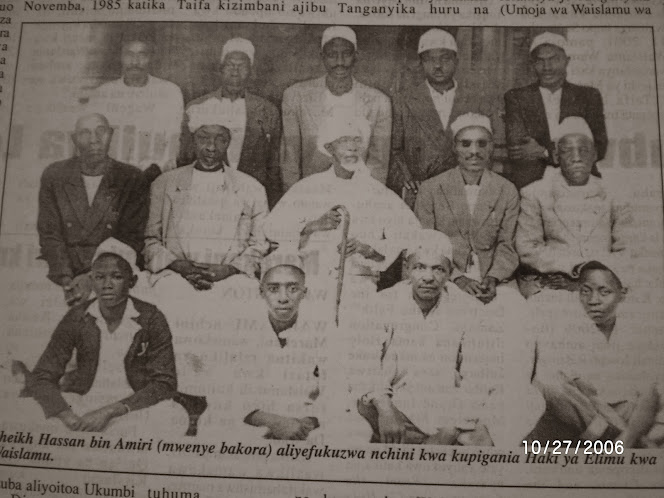

To make along story short Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir was arrested and deported to Zanzibar Paris Dar es Salaam

Soon after the deportation of Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir the government convened a conference which was known as Islamic National Conference. The main agenda of the conference held in Iringa from 12th -15th December was to discuss a constitution for a new Muslim organisation. And this is how BAKWATA came to be imposed upon Muslims. A dark cloud had fallen over Muslims of Tanganyika. The EAMWS Islamic University project of which construction had begun stalled for lack of leadership and the school projects in the provinces were curtailed for good. Since the formation of BAKWATA Muslims are still struggling to organise outside the central authority. But what is heartening is the fact that Muslims have refused to recognise BAKWATA as a representative of the umma. [19]

Since Mufti Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir’s deportation in 1968 the Mainland has had two BAKWATA Muftis. They have simply been ignored by Muslims. The office of the Mufti under BAKWATA instead of drawing respect has earned scorn, contempt and ridicule from the umma. To date no Mufti has been able to wear Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir’s ‘makbadh’. BAKWATA as an organisation is literally dead. Its stand to appease the government and to distance itself from each and every Muslims issue has made it irrelevant.

Conclusion

Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir lived his last years in Zanzibar Zanzibar Tanganyika Tanganyika

TANU the party he had worked hard to popularise and establish in the country during the struggle for independence did not announce his death nor did it send representative to his funeral. The government controlled media was silent about his death. The announcement of Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir death went by word of mouth from one Muslim to another and from one mosque to another, from one village and town to the next; just as he had during his lifetime moved from one place to another spreading the message of Islam and at the same time mobilising people to support TANU and fight for independence.

With the omission of Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir in the country’s history, Tanzania Tanzania

Islamic Propagation Centre (IPC) in Dar es Salaam Tanzania Tanganyika Tanganyika

Epilogue…

Two years after deportation of Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir…

In 1970 Nyerere invited to the State House the then Secretary General of the Tanzania Episcopal Conference, Fr. Robert Rweyemamu and the Pope’s Representative to Tanzania

The book is banned in Tanzania

The Church particularly the Catholic Church is in control of the Government by proxy. Through unseen hands it manipulates[21]the political system in such a way its influence permeates everything from the mass media to selection of students to secondary schools, institutions of higher learning, securing scholarship, employment, promotion for political office etc. etc. In short it is in control of the Executive, Judiciary and the Legislature. This is the reason the political system has been able manipulate the law with impunity as far as in effects Muslim interests, it has been able to ignore serious petitions submitted to the President, Prime Minster, and the Parliament by Muslims, it has been able to control and shape public opinion against Muslims.

Through research and many years of observations it is now possible to know a little how the unseen hand works. It works like a secret society and yet it is not one. It works in a two prong fashion. It has agents in all important institutions of the civil society who co-ordinates their activities when the need arise forming what could be identified as the ‘Christian Lobby’ similar to the powerful Jewish Lobby in The United States. The Christian Lobby in Tanzania

The dirty work for example, to order force to be used against Muslims or to undermine a Muslim in an important position who it is to the interest of the Church that he be dealt with, such tasks will always be apportioned to these Muslims in the Christian lobby. The Mwembechai tragedy rose from the hand of a Muslim. The campaign against the late Prof. Kighoma Malima in the media was spearheaded by a Muslim just to mention a few examples. These Muslims can be found in the media, echelon of the ruling party, the government, the police etc. etc. These Muslims are well rewarded and are a government into themselves. Unique in these Muslim personalities is the fact that they endure the political system. They are the show piece to display to the Muslim majority that the government does not discriminate, if it was those faces would not have been there. This system has now become self- propelling. It can work independent of whoever is in command, as seen in the ten year period (1985-1995) when a Muslim president, Ali Hassan Mwinyi was in power.

[1] This is a challenge worth taken by students to research into the tarikh of Muslim patriots who fought for independence but their contribution has not been requited.

[2] See Issa H. Ziddy, ‘Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir As – Shirazi (1880 – 1979) Mchango wake Katika Kukuza Taaluma na Maendeleo kwa Waislam wa Afrika ya Mashariki’ p.8.

[3] From his own mouth Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir declared himself a politician. See Sheikh Hassan bin Ameri, ‘Ubaguzi wa Elimu’ Waraka wa 1963 kwa Waislam wote wa Tanganyika

[4] See Issa H. Ziddy, op. cit. p. 18.

[5] Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir wrote the following books from 1914 to 1979: A’qdul A’ q – yaani a’ la mauled Jaylaaniy, (Cairo 1946), Wasilatul – Rajaa (Cairo 1951), Fat – hul Kabiir Sher – he Al – Mukhtasari Swaghiir (Zanzibar 1955), Madarijil – U’ laa Sherhe Tabarak Dhil – U’la (Cairo 1962), Sher-he At’ yabul Asmaau, Maslakul Muhtaaj ila Bayaani Istilail Minhaaj,(Cairo 1966), Idh’ahu Limaanil Asmai, (First publication date unknown reprinted Cairo 1987).

[6] The memorandum which bears Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir’s signature together with signatures of other patriots is among historic documents which it is believed have been destroyed to pave way for official history and can now no longer be consulted.

[7] For a detailed discussion on the subject see Cranford Pratt, the Critical Phase in Tanzania London

[8] Local historians most of them Christians including Nyerere himself want people to believe that TANU was the brain child of Julius Nyerere. To date the country has not honoured the founding members of TANU who most of them were Muslims. See Fr. Peter Smith, ‘Christian and Islam in Tanzania Development and Relationships’ in Islamochristiana, 16 (1990) pp. 171-182. Also Smith, ‘Some Elements for Understanding Muslim-Christian Relations in Tanzania’. 1993 (seminar paper presented in Dakar , Senegal London

[9]See Elder Council Section File 376, Party Archives, Dodoma. In 1970 Nyerere attended a seminar on religion in Tabora organised by the Tanzania Episcopal Conference (TEC). In that seminar Nyerere for the first time publicly addressed himself to the issue of TANU’s religious identity. Nyerere said ‘Our Party, the TANU, has no religion. It is just a political Party and there are no arrangements or agreements with a particular religion’.In pre - independence Tanganyika TANU had a religious identity and that identity was Islam just as CCM gradually assumed strong Christian influence, identity and excelled in its anti Islam posture.

[11]In the formative years of TANU (1954 – 1958) the top leadership in TANU was from Al Jamiatul Ismaiyya fi Tanganyika Tanganyika University of Minneapolis

[12]Mwafrika, 3 rd October, 1959.

[13] Soon after independence the government passed the Detention Act of 1962. This Act was passed in order to put into custody or ostracise to remote places those which the government perceived were a danger to peace and security of the country.

[14]Taarifa ya Kamati ya Utendaji EAMWS Mkoa wa Tanga 23rd October, 1968 , Ripoti ya Sheikh A.J. Jambia.

[15]Barua ya Mwenyekiti Halmashauri ya Uchunguzi Migogoro ya Waislam Kwa Waziri wa Habari na Utangazaji, 21st November, 1968 .

[17] When Inspector General of Police (IGP), Hamza Aziz, received the order from the Commander in Chief through the Minister of Home Affairs to arrest Mufti Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir, he could not believe his ears. Unbecoming of the Force’s discipline he demanded to know the reason for the arrest of Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir. When he was told that the reason was subversion, he told the Minister that there must be a mistake somewhere. Inspector General of Police told the Minister to tell the President that it was not possible for him to carry out that order because he was not convinced with the allegations levelled against the Mufti. Inspector General of Police refused to obey the order of the Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces and the President had to order State Intelligence to arrest Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir. Sheikh Hassan bin Ameir was arrested in the small hours of the morning and was straight away taken to the airport where a military plane was waiting to take him back to Zanzibar

[18] The Standard, 20th December, 1968 .

[19] In 1993 in desperation and in its effort to salvage BAKWATA the Minister of Home Affairs and Deputy Prime Minister Augustine Mrema convened a meeting between Muslims and Christians at the Diamond Jubilee Hall, Dar es Salaam Dodoma

[20] See Elimu ya Dini ya Kiislamu, Islamic Education Panel na Islamic Propagation Centre, Dar es Salaam 2000, pp 401 – 438.

[21] The government in 1970, having realised that Muslims were a majority in Tanzanian Mainland directed the Statistical Department to destroy all the 1967 census results so as to show Christians were a leading majority (See Family Mirror,Second Issue, November, 1994, p. 6).

Sheikh Ali bin Abbas mwanafunzi mtoto wa Sheikh Hassan bin Amir wakati alipokuwa anasomesha Dar es Salaam katika miaka ya 1950. Hapa yuko nyumbani kwake na mtafiti wa Kimarekani James Brenan aliyefika kumhoji. Sheikh Ali bin Abbas alimsaidia sana mwandishi Mohamed Said katika kumjulisha maisha ya siasa ya Sheikh Hassan bin Amir.

Labels:

release

05:42

TRACING THE FOOTSTEPS OF MWALIMU JULIUS KAMBARAGE NYERERE The Early Years in Dar es Salaam of 1950s

TRACING THE FOOTSTEPS OF MWALIMU JULIUS KAMBARAGE NYERERE

The Early Years in Dar es Salaam of 1950s

By Mohamed Said

L - R: Sheikh Suleiman Takadir aka Makarios, John Rupia, Julius Nyerere na Bantu Group 1955 It is a pity that Mwalimu Julius Nyerere did not reveal much of his early life in Dar es Salaam of 1950s of which he came to as a budding young politician fresh from Edinburgh University aged about 30 years old. Why Mwalimu Nyerere was secretive about his early days during the transformation of Tanganyika African Association (TAA) to Tanganyika African National Union (TANU) is now a rhetoric question because we can only speculate. Was Mwalimu trying to conceal something on his past or was that an innocent omission? The only time Mwalimu walked down memory lane was in 1985 at the Diamond Jubilee Hall where in an emotional farewell speech before he stepped down from the presidency he addressed Elders of Dar es Salaam who supported him during the struggle for independence. In that memorable speech flavored with Mwalimu’s oratory skills he walked back into history and paid tribute to Wazee wa Dar es Salaam (Dar es Salaam Elders) who supported him from day one since the founding of TANU in 1954. In his revelations Mwalimu Nyerere for the first time in public mentioned two other patriots forgotten in the history of Tanganyika. He said that in those difficult days the other young men with him were Abdulwahid Sykes and Dossa Aziz. Abdulwahid was TAA president in 1953 and was among the the four financiers of the movement along with his young brother Ally, Dossa and John Rupia. Abdulwahid died young in 1968 but Dossa went on to old age but both of them died the fruits of independence of which they had worked so hard having passed them by their names hardly associated with TANU, Nyerere or the independence movement. Dossa died a poor and lonely man at Mlandizi in 1997. One can write passages and passages on contributions and sacrifices made by the two Sykes brothers – Abdulwahid and Ally and Dossa; and the elders like - Mwinjuma Mwinyikambi, Kiyate Mshume, Jumbe Tambaza, Sheikh Hassan bin Amir, Sheikh Suleiman Takadir to mention only a few. In those days these names made up ‘who is who’ of the municipality. These were the rich and the famous of the town. But to understand the town, its elite and politics one has to revisit how colonialists demarcated Dar es Salaam.

| ||||||